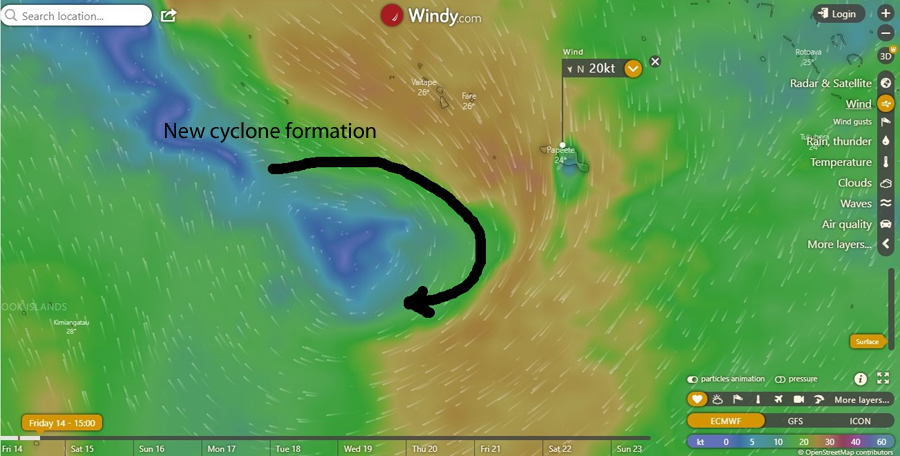

Today, the sun came out. It is the first time we’ve seen the sun in about seven days. It’s been raining. And I mean, raining! I’m talking about days and days of tropical storm-like hard relentless rains. We have a low-pressure system over us that will eventually turn into a cyclone as it moves away toward the west.

This lifestyle is not all sipping drinks at sunset. Sometimes it can be downright challenging. The GFS forecast had us smack in the middle of a developing cyclone. And, to frighten us even more, the forecast called for a direct hit from another cyclone in 6 days once the current system moved away. Yikes!

Tahiti sits right on the edge of the cyclone zone. It is not immune to cyclones but during La Niña years, cyclones are rare events. El Niño and La Niña are climate patterns in the Pacific Ocean that can affect weather worldwide. A description of both and the effects of weather can be found here. This is a La Niña year but it doesn’t mean we can avoid watching the weather closely.

When you live on the water, watching the weather is about the same as a mutual fund manager watching the stock market and the economy. It affects every aspect of our lives. We often find ourselves, looking at the long-range forecasts and wondering how accurate they truly are. I have often said, weather prediction is a 3-day science. Past three days, the accuracy of the forecast models exponentially deteriorate. This is not to say they’re unhelpful. We see systems develop and identify the ones we need to keep watch on. And, this is very helpful. Inside of three days, forecasts tend to be more reliable. However, different forecasting models can often say different things often causing us to second guess decisions. This was one of those times.

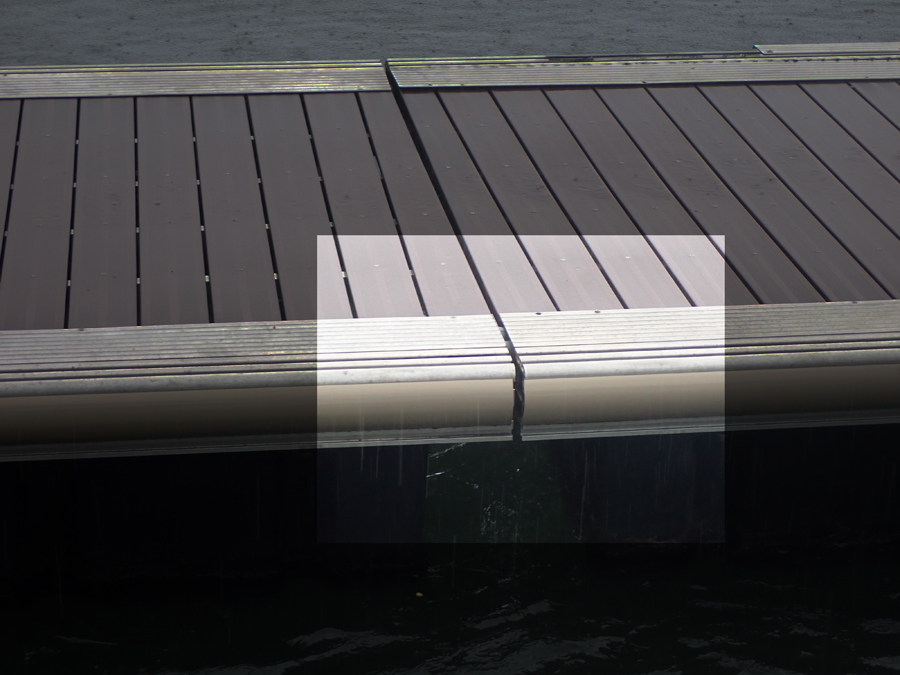

The marina in which we are currently located is not ideal for storms. In the event of a true cyclone or large tropical storm, this is the last place I would want to be. The construction of the docks is not very strong and the location of the marina is subject to swells and swirling water. In all honesty, I think this facility was another government project put out to the lowest bidder. It is actually fairly new and it’s a bit of a shame the docks are weakly constructed. In addition, the pylons upon which the marina floats only allow for about 1m (3 feet) of rise in water and in my opinion are not tall enough. If the docks float higher than this they float away and the marina is demolished. They could have done so much better.

Securing a line to the pylon is better than the dock cleat. Note the limited height of the pylon. This dock can only rise about a meter before it floats off. The empty slips in the background are because these are the weakest slips and boaters have left the marina.

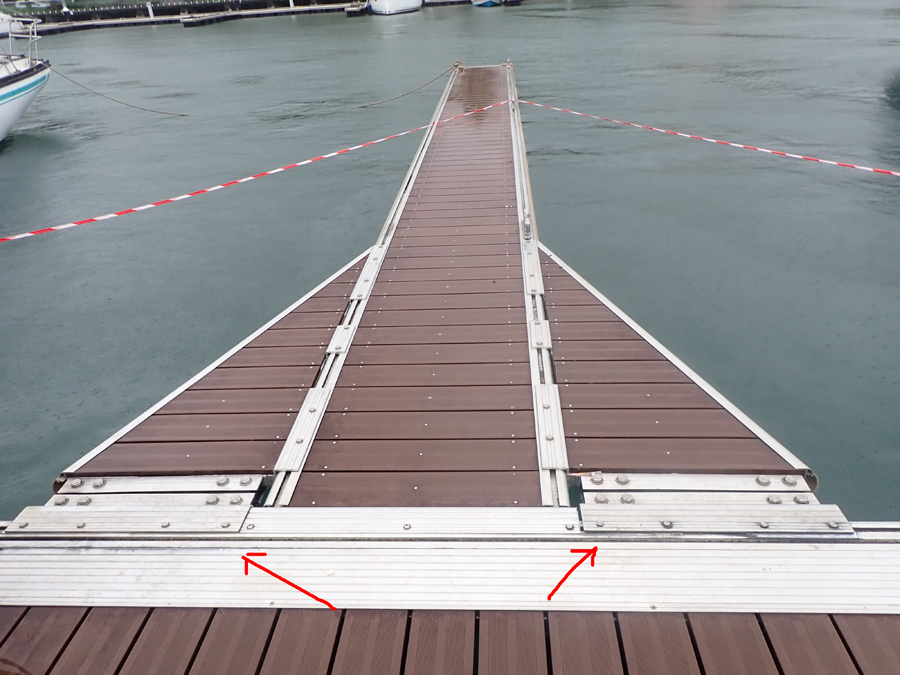

The weaker slips do not have a pylon at the end giving added support. This finger started to break away as the bolts sheared. The boats on either side had to quickly move.

Using fingers with a support pylon at the end adds an element of strength to the dock. But as we learned last year, this can also break.

Most boats try to fasten a line to the pylon even if it means going across the walkway. This is a good idea but can make walking down the dock a bit of a challenge.

A beautiful yacht called Imagine has long double lines on the back and front pulling it away from the concrete dock.

On Tahiti, Marina Taina is perhaps the safer marina for weather events but we like the location of Pape’ete so much more. And because of this, we realize in bad weather we will need to evacuate. However, it is worth it to us as we love being downtown and all the offerings. And besides, 99.9% of the time our marina is perfectly safe.

We have several safe evacuation options available to us. Our most likely choice is Phaeton Bay about 25 km (38.5 mi) away. It is easily reachable in one day but we need to decide about 3-5 days ahead of a weather event so we are not moving in deteriorating weather. And, what did I just say about the weather? It’s a 3-days science. So when we are faced with forecasts that are pure polar opposites, deciding on which one we think is best can be challenging.

Some of you might be thinking if Phaeton Bay is so safe why is it we don’t anchor there all the time? The simple answer is, there’s nothing there. There is the small town of Taravao and an awful lot of mosquitoes. That’s about it. It also rains in that area of Tahiti quite a lot more than Pape’ete but this week that wouldn’t have been very noticeable.

Waves and swells are the determining factors for our decision to stay or leave. If waves and swells are in any direction other than the northwest, conditions in the marina are usually calm. The forecast showed waves and swell to be large and from the northwest. Not good. On the GFS forecast, it looked horrible. On the ECMWF model, it looked bad but most of the weather seemed to be west of us. So, who do we believe?

The Global Forecast System (GFS) is a US National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) weather forecast model that generates data for dozens of atmospheric variables, including temperatures, winds, precipitation, soil moisture, and atmospheric ozone concentration. ECMWF is the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts and is often referred to as the Euro Model. The ECMWF center has one of the largest supercomputer facilities and meteorological data archives in the world.

ECMWF upgraded their forecast models and really proved themselves during Hurricane Sandy. They were the only true predictor of this storm and showed a path completely different from all other models. The almost unprecedented and sudden ‘left hook’ of the storm towards the coast of New Jersey was attributed to interactions with the large-scale atmospheric flow. This led to speculation that satellite observations may play an important role in the successful forecasting of this event. They were the only correct one. You can read more about this here.

I think many sailors will agree, statistically speaking, the Euro Model is the best forecast followed closely by GFS. When our neighbor in the marina said he was leaving for Phaeton Bay this solidified our decision to stay put. Not because we disagreed with him but because we knew with him out of the way we’d have more room to secure the Puffster with longer lines allowing us to move about in the slip. It also meant we could secure lines to the pylons instead of the dock cleats. The dock cleats are a weak spot of all marinas.

As Cindy always says, we plan for the worst and hope for the best. As soon as our neighbor pulled out, we began the process of securing extra lines. It has already started to rain at this point and we worked in our bathing suits. Believe it or not, this is much better than working in the hot sun that is normally here. We are now 3-days from doomsday. The trick in this marina is to tie to the strongest part of the dock which means the main walkway and not the pier fingers. We double up the lines. No matter which direction Cream Puff moves, there are at least 3 lines holding her. If we do it right, the lines all tighten at the same time so one line doesn’t take the brunt of the strain. For some reason, sailors refer to ropes as lines. Sorry about suddenly getting nautical on you.

In the video below, note the flag is hardly moving as the wind is very light at this time. All of the boat’s movement is caused by the surge in the marina as the ocean swells enter the harbor about 1.75 km (1.1 miles) away. The surge causes whirlpools and can violently move the boat. We tie the Puffster so it doesn’t constantly slam into the dock (on the left side). If you don’t see the video below, click here.

We try to keep the lines as long as possible because they stretch as the boat pulls. The stretch in the line reduces shock on the boat cleat (the attachment point). On the shorter lines, we use special springs to help reduce shock. These springs are backed up by a safety line in case the spring should fail.

It takes us most of the morning to systematically place each line and feel comfortable with our efforts. During this time about 30 % of the boats in the marina departed. It is the emptiest we’ve seen this place since arriving here. With the gray skies and open slips, it’s a little bit eerie and far from the normal sunny days and light breezes fluttering the palm trees on the shore.

The swells came in a predicted and after a couple of days, we know the ECMWF forecast was the least wrong. Interestingly, a forecast model called ICON also proved true. ICON (Icosahedral Nonhydrostatic) is a model created by the German Weather Service. In Europe, it is generally considered to be even more accurate than the ECMWF due to the better resolution. But in the South Pacific, it is normally considered less reliable than ECMWF. This meant, most of the nasty winds passed west of us.

The marina likes it when boats leave during bad weather. It saves on the repair bill for their docks. Last year during a small storm, our dock pier finger broke during the night. Based on this, we knew how to tie Cream Puff with less stress on the dock. Others weren’t so lucky and a couple of docks broke making the owners scramble to find a safer slip.

On the opposite dock from us, one of the larger fingers came apart as ours did last year. It was towed away by the port authority. The boats here had to quickly move.

What is life like on the boat during these events? Well, it is quite uncomfortable. The rocking of the boat is tolerable and doesn’t seem to bother Cindy or me. If anything, it makes us sleepy. But, when the surge pushes the boat in one direction and it yanks on the line, the jerking is enough to knock a person off their feet. We try to spend most of the day sitting down and both laughed about being bounced off the walls in the shower. It is not uncommon to be tossed into a bulkhead leaving a bruise. We call these “love bumps”.

Sleeping can be a problem. Again, the hard jerking of the boat can wake us up during the night. We also hear the lines creaking on the boat cleats as they tighten with the strain. This can be solved with earplugs. But, using earplugs opens another can of worms. Will we hear the sound of something going wrong during the night? On the third night of this low weather system, things started to ebb a little bit. Finally, I got a good night’s sleep. I actually slept until almost 7 am. This is so unlike me. I’m normally up at 5 or 5:30 at first light. This is when I realize we had a tsunami.

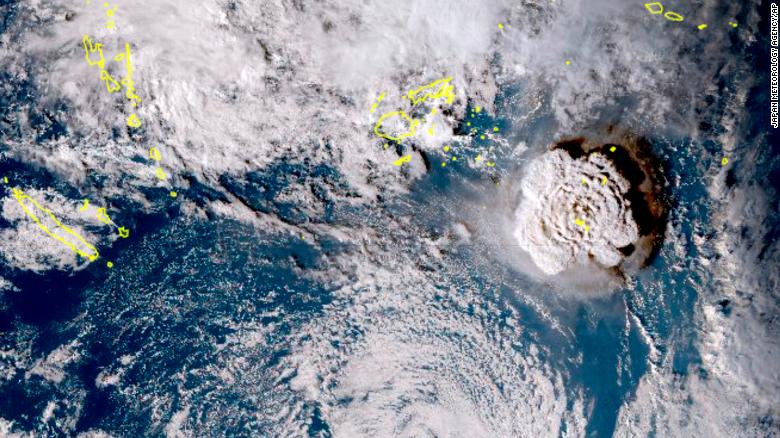

Yes, we had a tsunami! I’m sure by now you’ve heard about the event near Tonga where an underwater volcano erupted sending shockwaves in all directions. Well, we are only 2,700 km (1,700 mi) from Tonga. In comparison, the USA is three times further away, 8,500 km (5,300 mi) and they issued tsunami warnings all up and down the west coast. Here, we didn’t get a warning. And, quite a few people are angry about it.

A satellite image taken by Himawari-8 a Japanese weather satellite captures the volcanic explosion. The islands of Tonga are outlined in yellow.

The local government agency responsible for tsunami warnings responded to the anger of local citizens by stating the islands were already under a red vigilance warning due to the tropical system hovering over us and didn’t see the need to alert people further. They had already issued warnings because of the large ocean swells. I’m not sure how I feel about this. Remember me telling you that a tidal surge of more than a meter could float the entire marina off the pylons? The rise in water due to the tsunami was estimated at 0.8m!

Tsunami warnings are taken very seriously here. In the Pacific rim, earthquakes can occur at a rate of one per week. Most go unnoticed. Some can be severe and trigger large tsunamis causing massive devastation. If the alarm sounds here, people will literally run for higher ground. They don’t go to the beach and hope to capture something on video to post later on YouTube. They don’t dust off the surfboard. A tsunami warning means run for your life and get away from low-lying areas! This is island life in the ring of fire. So why didn’t the alarms sound? Underwater volcanic eruptions are harder to measure than eruptions on land: another tidbit pointed out by French Polynesian authorities. Therefore a dangerous tsunami can be harder to predict if from an underwater origin. Is this a valid excuse? As I write this, I’m still not sure if the alarm should have sounded, or not.

Offshore, just outside of the surrounding reefs, waves during the tsunami were estimated to be in excess of 3m (9 ft.) and swells were 2m (6ft). These are averages meaning there are some waves and swells considerably higher. Would another rise of less than a meter really be notable? Perhaps not offshore. But in coastal areas and bays, it probably would be a concern. I guess we’ll never know the local effects of the Tonga volcano tsunami or the rise of water in the marina since we slept right through it.

We are safe, for now. This coming week we’re off to explore and hopefully can stay dry.