Wow. In the last post we talked about our drive along the Great Ocean Road. Our timing turned out to be perfect. Due to massive wildfires followed by torrential rain, flooding, and landslides, the road is currently closed in both directions.

We left off in the wonderful little town of Warrnambool. We crashed here for a couple of days in our Airbnb. Over time, we have learned to build “rest days” into our travels. Being retired, there is really no hurry to jam everything into a single day. If we spend a couple of days on the PC or watching mindless TV, we are perfectly fine with that. Taking a break from driving was also very welcome.

Back on the trail, our next stop was Adelaide. Adelaide surprised us in the best possible way. It is a walkable city that is easy to get around and pleasantly uncrowded. We stayed in the city center with great cafés scattered everywhere, and literally across the street were the Central Market and Chinatown.

Our Airbnb was located on the same block as Her Majesty’s Theatre. After parking the car, I noticed the theatre and made a mental note to see what was playing. We both love live theatre, and being in an English speaking country means we can actually understand the show. Maybe something Australian themed to soak up a bit of local culture. Ha. That is not exactly how it played out.

We did manage to score tickets that night, and the show turned out to be fantastic. It was a musical built around Dolly Parton’s music. Dolly is a gay Aussie man’s idol, and when his boyfriend breaks up with him during Covid, she appears in his imagination. It was weirdly complicated, very entertaining, and genuinely funny. The actress who played Dolly had an incredible voice and absolutely nailed the role. She even sang “I Will Always Love You.” Maybe not quite Whitney Houston level, but honestly, it was darn close.

The old port town offers a glimpse into Adelaide’s working past. There is a maritime museum, which we passed, and a very walkable area filled with cafés and old buildings. One of our Aussie friends suggested we add the port area to our list, and we are very glad we listened. It was well worth a day of wandering.

At this point, we had visited four of Australia’s six states. Australia has six states, New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania, along with two territories, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory.

During this leg of our journey, we edged up against some of Australia’s wine country. Grape vines stretched as far as the eye could see. We both wondered how this compared to Napa Valley or even France. Google came to the rescue. Size wise, the difference is dramatic. Napa Valley covers roughly 750 square miles, and even France’s most famous wine regions are relatively compact. By contrast, Australia’s major wine regions together span tens of thousands of square miles. Where Napa can be driven end to end in an afternoon, Australian wine regions can require hours, or even days, just to move between them.

After Adelaide, we continued north and west for our next adventure. We were headed to an opal mine. That decision took us to the opal capital of the world, Coober Pedy. From Adelaide, we psyched ourselves up for a nine hour drive into the outback. Coober Pedy truly sits in the middle of nowhere.

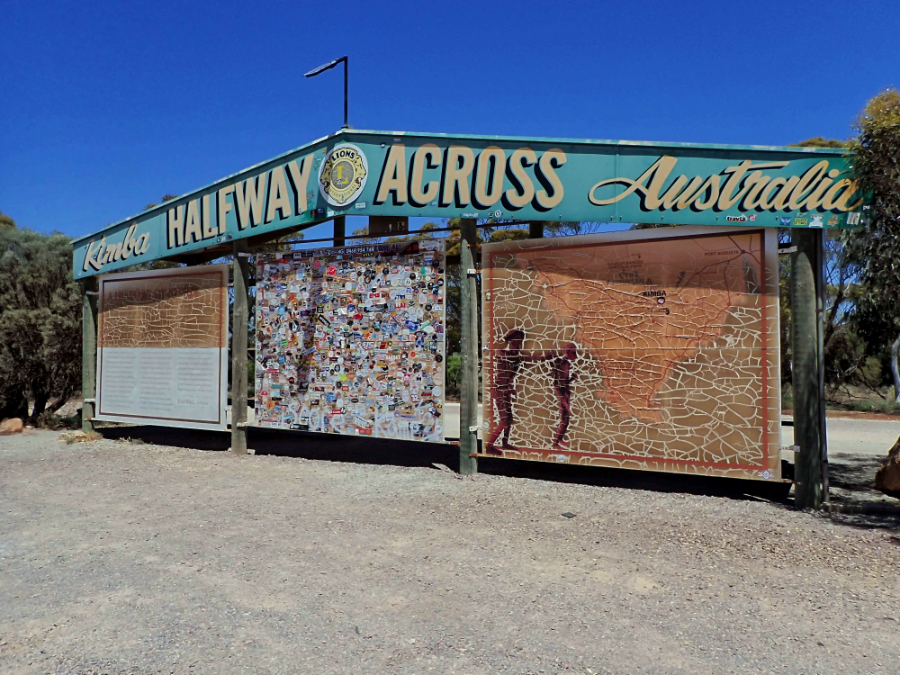

Our first pit stop was Port Augusta. This is the last real town on the route, so we made sure to fill the tank completely. From here, we should be able to reach our destination on a single tank of fuel, about six hours away. About an hour and a half into the drive, we passed through a very small town called Kimba. Its claim to fame is being the halfway point for people crossing Australia. There is even a giant eight metre tall statue of a galah beside the highway to mark the spot.

We stopped to stretch our legs and use the public restrooms, then hopped back in the car. At this point, we had been driving for about five hours and started wondering how much longer we had to go and what our ETA looked like.

I should pause here to explain that GPS reception in the outback is intermittent at best. Since we were on the same road for hours, we decided to turn it off to save data. What was the point of GPS when there was literally one road. As it turns out, this was a costly mistake.

If you look at a map, Kimba is not on the way to Coober Pedy from Port Augusta. When we reopened the GPS app, it told us we still had seven hours to drive. Back in Port Augusta, before we closed the app, it had said five and a half. How could it be more and not less? How were we not closer?

You guessed it. We had missed our turn and driven an hour and a half in the wrong direction. After some head scratching, we realized our only option was to drive all the way back to Port Augusta, adding three hours to what was already a long day. Roads are scarce out here, and with Gawler Ranges National Park between us and Coober Pedy, there was no shortcut. Sigh.

When looking at Google trying to figure out where we were, Cindy found this image and thought it might be interesting to read about the town. We drove all the way here – why not look around?

Kimba town landmark is a giant pink and grey galah parrot. You can’t miss it. We often see galahs on this trip.

Back in Port Augusta, we topped off the tank again and made absolutely sure we were on the correct road. This pushed our ETA back another three hours and meant the final stretch would be driven in the dark. Most Australians will tell you this is a bad idea. Kangaroos love the roads at night.

As the sun set, we caught up to a police car doing exactly the speed limit. We were going just a tad over, so we happily tucked in behind him. It felt like a safety buffer. If a kangaroo jumped out, chances were he would hit it first. As it got darker, the officer slowed even more. Yep. He knew exactly what he was doing.

We followed that police car for the last couple of hours into Coober Pedy. It did not bother us that we could not see much. We figured we would see it properly when it was time to leave. And honestly, the outback is, well, the outback.

Our home in Coober Pedy for the next three nights was an underground house. In Coober Pedy, people live underground for one very practical reason. Heat. Summer temperatures regularly push past 45°C (113°F), and long before air conditioning existed, locals discovered that carving homes into the soft sandstone kept them naturally cool year round, hovering in the low to mid 20s (low to mid 70s°F). These dugouts are quiet, dust free, and incredibly energy efficient, shielding residents from brutal sun, desert winds, and flies. What started as a miner’s necessity has become a defining way of life.

It is probably not what you are imagining. Most homes are built into hillsides. You do not climb down a mine shaft to get to your living room. What surprised me most was the complete loss of time awareness. Most rooms have no windows. Only the entrance and front façade let in daylight. At one point, I was sure it had to be around 10pm and started thinking about bed. Then I walked into the kitchen and discovered it was still light outside and only 8pm.

Dead quiet. That is the best way to describe living underground. Turn off the TV and the air conditioning and there is nothing. Absolute silence.

The next day was the real reason we drove all the way into the outback. Coober Pedy is the opal mining capital of the world. That is the reason the town exists at all. People here are miners, family members of miners, or somehow tied to the mining industry.

Stepping out of our underground home, we took in the view. Everywhere we looked were mines. Some were large underground tunnel systems. Others were nothing more than a hole in someone’s front yard, sometimes marked only by a windlass, a pile of white spoil, and a hand painted warning sign. In Coober Pedy, the ground itself tells the town’s story. Fortunes chased, abandoned, and chased again, often just metres from where someone is cooking dinner or parking the ute.

We headed off to tour a mine. The Old Timers Mine museum is easy to miss. From the front, it barely looks like anything at all. Just a modest entrance in a dusty hillside. Then you step inside and everything changes. Almost the entire place is underground. Tunnels branch off into rooms where miners once lived, cooked, slept, and worked, all carved by hand. It is not slick or theatrical. It feels close, practical, and slightly claustrophobic, which is exactly the point. This hidden underground world was simply everyday life.

After paying the entry fee, we were offered hardhats. They were not mandatory, but the woman behind the counter strongly suggested them due to low ceilings. I have already had enough hard knocks in life, so it seemed wise to avoid more. I am very glad we wore them. We both hit our heads at least six times each.

Being an opal miner was hard, patient work done in near darkness. By candlelight, miners swung pick axes into sandstone, following faint hints of colour and hoping the next strike would change their lives. The air was hot and dusty, the spaces tight, and progress slow and uncertain. It was physically exhausting and mentally draining, with no guarantees at all. To be honest, it was a pretty miserable life, especially for those who never struck it rich.

The tour is self-guided. It begins in the mine itself, continues through a small museum, and concludes with a glimpse of the underground living quarters. And like all museums, you exit through the gift shop. Unsurprisingly, they sell opals. Imagine that.

The opals were actually high quality and reasonably priced. We took advantage of that, and Cindy picked out a necklace I chose for her. An opal wrapped by a silver snake.

Can you imagine digging by hand with a pick ax and using only a candle for light while lying on your belly? No thanks.

This made me stop and think. Yes, the miners had kids. Not exactly what most kids would imagine for their room

We spent the rest of the day wandering around Coober Pedy. That did not take long. The town is essentially one main street, and everything else is either underground or a mine. Still, we can now say we have been inside an Australian opal mine and have an opal to prove it.

I swear, I am not making this up. These painted tires are on the list of things to see in Coober Pedy

When walking the trail up to this sign, people walk over somebody’s home. The pipes you see are vents to the underground home

The next morning, we left after breakfast and faced a three-day drive back to Melbourne to return the rental car and fly back to the Puffster. During our wanderings around South Australia, we drove about 4,140 km (2,570 miles) over three weeks. That is roughly equivalent to driving from New York City to Los Angeles. We were more than ready to be out of the car for a while and very much looking forward to sleeping in our own bed again.